- Home

- Mario Sabino

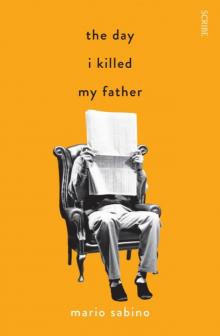

The Day I Killed My Father Page 9

The Day I Killed My Father Read online

Page 9

I’m fine, thank you. No, the dizziness didn’t come back; it was all in my mind. We can talk. Don’t worry, I’m back under control. My uncertainty has gone, and everything is clear again.

Let’s get straight to the point. I told you that reading my book would help you understand some of my processes. Some. And these processes are intellectual … Go ahead … Antonym says at one stage that his father isn’t worth it. So what? It’s a line — laden with self-reference, I admit — that only reinforces my intention to distance myself, through writing the book, from the real relationship that consumed me.

Don’t look for clues in the plot itself, please. That’s vulgar. What I have to say is of much more interest to you. And it will make everything clearer. You want clarity, don’t you?

I wanted, as I’ve said before, to speculate about the birth of Evil, after I’d acquired some knowledge of philosophy, literature, and existential matters … What? I don’t mean to offend you, but that’s a narrow view of the matter. Try to be less of an analyst and more of a philosopher. It is true that science explains that we are born with genetic determinants which can be developed or stifled by our environment. It is also true that psychology can provide explanations for my blasphemies when I was a boy, and much of what followed. But that’s not my point. It’s more transcendental than that. I was interested, I repeat, in finding out what lies beyond our genes, and their psychological or social triggers.

Let’s take a historical case: Hitler. Some people believe that his artistic frustrations and repressed homosexuality led him to do all those horrific deeds, as if they had activated hypothetical genes for Evil. But if they were the only factors, there would have been hundreds of monsters of Hitler’s calibre throughout human history — and there haven’t been. Hitler’s followers? They only confirm my theory. They were so petty that they would have been insignificant, or would only have been common criminals, were it not for Hitler. Now, consider the opposite: Good. Take the example of Saint Francis of Assisi. In an era of utter moral and religious decay, he renounced wealth to assume a life dedicated to Christ and the poor. He attracted thousands of followers, but there is no record of any of them having attained the same degree of sainthood and abnegation. Can hypothetical genes for Good explain Saint Francis? If that were the case, shouldn’t there be lots of others like him?

Where am I going with this? Well, you read Future. I’m suggesting that there are men of spirit, good ones and evil ones, who are granted complete free will. It is men of spirit who drive humanity and, one way or another, who fulfil God’s designs … How can divine designs and free will coexist? That’s the point I’d like to have elaborated on in my book: God’s designs are universal, but they are brought to fruition by the free will of special individuals. In other words, there had to be a Saint Francis, just as it was imperative that there be a Hitler, so that humanity could follow the path laid out by God. But Saint Francis only became Saint Francis, and Hitler only became Hitler, because they were given the ability to choose. The former chose Good; the latter, Evil. Which also means that Saint Francis could have chosen Evil, and Hitler, Good … Yes, in a way, they were equal at some stage. That’s another heresy for my list.

You’re right; most people choose their own path. But, unless they’re men of spirit, their power is undeniably limited by inner forces, by the instinct to follow the herd. For them, their will isn’t as free as they think it is. That’s what allows God to forgive the sins of the small … I beg your pardon? Can a monster like Hitler be forgiven? Well, based on the assumption that his entirely free choice is a part of the divine plan, I believe so. As it says in the last chapter of Future, Good and Evil are parallels that meet at the infinity that is God. But perhaps the idea of forgiving men of spirit who choose Evil is beyond human understanding.

My ability to converse with literary and philosophical traditions? You’d make a great literary critic, you know. You’ve perfected the art of saying nothing while creating the impression that you’re saying everything. The sarcasm again — forgive me. Remember the passage where I write that Antonym, to pass the time, liked to make free associations? Well, his favourite association is actually a line from a commedia dell’arte character, Il Dottore. That’s what dialoguing is: stealing.

What would have become of Antonym? He believed himself to be a man of spirit, but he wasn’t really. If I’d continued the book, Antonym would have formed a trinity with Hemistich and Farfarello. His baptism into the darkness of the religion of the senses would have been to kill Kiki, in a ritual similar to the one in which Augusto killed his wife. The aboulic, mistrustful Antonym would transform into an eloquent preacher, with an enormous talent for drawing people with money to the new religion. The enthusiasm of neophytes, you know.

Thanks to Antonym, the orgies would become more and more fantastic, and the evil ones would build a kind of cathedral of pleasure, far from the city. The success of the undertaking would attract the greed of extortionists connected to the police, and of those who dealt in the hallucinogenic weed that animated the parties. The situation would get complicated. To stop the business from crumbling, Farfarello would suggest to Antonym that, without Hemistich’s knowledge, he should approach the senator he had blackmailed in the first place. Using his great influence in the highest spheres of political power, the senator could help get rid of the extortionists.

Antonym would take Farfarello’s advice, and would be told by the politician that he’d only intervene if Hemistich were eliminated — the senator would want to take revenge against he who had blackmailed him. Antonym would hesitate, but Farfarello would convince him it had to be done so they could both be saved, and because of their undertaking. Antonym would then kill Hemistich, after a conversation in which Hemistich would offer himself as a sacrificial lamb. I had a draft of this dialogue, but I lost it. Anyway, after killing Hemistich, Antonym would receive a videotape, delivered to his home. Farfarello had filmed the murder, and would give a copy to the police if Antonym didn’t disappear without a trace, leaving the entire business to him, Farfarello.

Disoriented, Antonym would return to the beach, where he’d discovered, or thought he’d discovered, that he was a man of spirit. There, faced with the realisation that he was really no more than a cold-blooded assassin, he’d drown himself.

‘Another future dissolved under nature’s mantle of silence.’ That’s the sentence with which I was planning to end the chapter … What would happen to Farfarello? It would be clear that he had triumphed. Farfarello had masterminded everything: the blackmailing of the senator, Antonym and Hemistich’s meeting, Antonym’s conversion, the extortionists, the senator’s demand that Hemistich be eliminated, Hemistich’s murder — and, to an extent, even Antonym’s suicide … No, he wasn’t a man of spirit who had chosen the path of Evil. Truth be told, Farfarello was the Devil himself. He had materialised to play with two tiny, pretentious souls — Hemistich’s and Antonym’s. The name Farfarello, in fact, is a scholarly clue — it is another word for the Devil in early Italian literature.

Go on, ask … Have I ever believed myself to be a man of spirit, like Antonym? I repeat, I could have chosen to spare my father and myself … The entirely free will that is an attribute of men of spirit? I know where you’re taking this. I’d say I’d be a common criminal if I’d simply killed my father. But my philosophical motives for this act, and for what followed the patricide, belong to the sphere of the extraordinary. I was both the crime and the punishment. I beg your pardon? No, you’re wrong. Someone who kills, then kills himself, is the opposite. The last thing a suicide of this lowly calibre wants is to reap the punishment, do penance for his sin. He’s weak. I, on the other hand, am doing penance. I am confronted with my sin every single day.

–15–

I dreamt last night that I was a child and alone at home, feeling sick. I kept on vomiting, and there was no one to help me. Distressing. I did actually find my

self in this situation several times, after my mother died. Domestics never lasted more than a year at our place — my father fired them before they got to know us too well. As a result, I was always in the company of strangers who didn’t really care whether I was OK or not. They’d do their work, then disappear into the back shed in the afternoons, and they’d only come out to answer the door or fix an afternoon snack … My routine? I’d go to school in the morning, get home at lunchtime, eat alone, do my homework, watch TV, have afternoon tea alone, go for a swim in the pool, have a shower (I often didn’t bother, since no one kept tabs), eat dinner alone, watch more TV, and, when I heard my dad arriving, run to my room to pretend to be asleep. And I would end up falling asleep, obviously.

Whenever I was sick, like in my dream, it was our driver who came to my aid. But he wasn’t always at home, since my father used his services a lot. My pre-adolescence was very solitary, as was my adolescence … Yes, my father took me to doctors about my dizzy spells. They ran a series of tests, which detected nothing. The diagnosis was ‘neurovegetative disorder’, a name that doctors use when they don’t know what the problem is. Since they assured my father that I wasn’t going to die from it, he stopped worrying about my crises. I could miss a week of school, and he wouldn’t care. He’d go off to work and out on the town, regardless. The only difference on these occasions was that he’d allow his driver to put his other tasks aside and keep me company.

Did I have friends at school? It’s not that I didn’t, but I was never able to truly be a friend. Every now and then, someone would invite themselves over to my place after school. When this happened, I’d change the subject, or I’d tell them that the pool was being renovated, or that I had a doctor’s appointment. Stuff like that. It’s hard to explain. I didn’t like being alone but, at the same time, I was used to solitude. It seemed to be my natural state … Weekends? Well, when my father was out of town — and he was gone a lot — I’d keep to the same routine as every other day. When he was in town, we’d go to the country club. He’d spend the whole time drinking whisky with his friends, while I’d wander from one group of kids to the next, without settling into any of them.

No, my father had no family. I mean, he did, but he didn’t like having contact with them. He came from humble origins, and was irked by the fact that his relatives hadn’t broken out of the poverty cycle which had scarred him in his childhood. Actually, when I say relatives, I’m referring to cousins, aunts, and uncles. Both sets of grandparents, on my father and mother’s side, died before I was born; and his only brother, who was younger than him, had gone off to Australia without a trace. This uncle once tried to re-establish contact by phone, but my father had chased him off with swear words, according to the driver, who’d witnessed the scene …

My mother’s sister? Well, like I said, she lives abroad. She’s lived in several places: New York, Paris, Milan. She went because her husband, an executive with a multinational, was transferred around a lot. After he died, she moved to a small municipality an hour out of Rome, in the mountains — Anticoli Corrado. It’s very popular among sculptors and painters. This aunt of mine always had artistic inclinations. She makes etchings; some are interesting. Occasionally, she sends letters — which I don’t answer — and tries to get me on the phone, but I don’t take her calls. She feels a bit guilty for everything that’s happened … I could talk to her, I know, but the price I’ve imposed on myself is high. That’s the way it has to be.

–16–

When my mother was still alive, I read to acquire enough knowledge to impress her and humiliate my father. When she died, I abandoned my books for a good while. I only went back to them when I was about fourteen. I think I started reading again because it was a more efficient way to pass the time. I read so voraciously that, instead of toys and junk food, I used my hefty allowance to buy books. My father always gave me a lot of money. Not out of generosity, but insouciance. It was a way of saying, To hell with it. Let him look after himself. I had to start my collection almost from scratch, since one of the first things my father did when my mother died was donate most of her books to a charity — just as he did her clothes, jewellery, and all her other belongings. Even her photographs ended up with my aunt. I got them back as an adult, and keep them in the cupboard I have here.

I spent my adolescence reading — not least because it irritated my father, who blamed it for the fact that I’d turned into a skinny, pale teenager. At the country club, he couldn’t hide his envy of his friends who had strong, suntanned sons who’d already had a string of girlfriends, and who engaged in vile banter. To further set myself apart from them, I opened my mouth only to say that the days of the bourgeoisie were numbered, and that the only thing worse than robbing a bank was founding a bank. Not that I was some snot-nosed wannabe communist. I’d read the Communist Manifesto, and other nonsense of that sort, just to have ammunition when I wanted to provoke my father and his rich friends. It was more or less like wearing torn trousers and dirty t-shirts, which I also did.

Concerned that I wasn’t like the idiots he considered models of healthy youth, my father decided to, in his words, ‘help me become a man’. He started bringing up smutty subjects, and one night dragged me off to a ‘special restaurant’ — an upmarket brothel. ‘Take your pick, and I’ll pay,’ he said, showing me the girls. To get out of it, I pretended I was dizzy, really dizzy, and that I’d faint if I stayed. My father obviously didn’t fall for it. He only agreed to leave because he didn’t want to risk becoming a supporting actor in a ridiculous fainting scene. On the way home, he hurled insults at me. He said I was a poof, abnormal, sick, and that he’d never go out in public with me again. Not even to the country club.

To my immense satisfaction, he kept his word. We only went out together again when I started seeing the woman I eventually married … How old was I when I lost my virginity? It was after my father tried to initiate me — I was about seventeen and a half. I went by myself to a downtown brothel. The whore I chose had a broken arm, and after we had sex, to complete the hour I’d paid for, she started telling me a weird story. She said that where she came from, there were women who gave birth to children who were half human, half animal. She must have been crazy.

Coming back to my reading … I read so much that it affected my performance at school. I neglected my studies to concentrate on novels, short stories, and plays — some of them impenetrable to a teenager … Did my books make me happy in any way? On the contrary, they helped me to become even unhappier. But it was a special unhappiness; that of one who believes himself better than others. Turning to books to make oneself feel especially unhappy — there’s nothing uncommon about that. I’d even go so far as to say that it makes the most sense. I don’t want to dwell much on this, because it’s not our topic. I’d just like to say one thing: I think literature confirms human unhappiness for those who are already prone to it. Or, at least, it shows how limited happiness can be. It’s possible to compose beautiful symphonies overflowing with the purest joy, and to paint magnificent canvasses in which radiant morning light is the only protagonist. But there is no great book whose main subject is not unhappiness … Why is that? Because one must be unhappy, in essence, to write a book, and to seek, in the interregnum of writing, some happiness. Clarice Lispector, remember? And me.

The ironic thing is that, because of my devotion to books, I ended up living the illusion that I could be happy full-time. It is an indirect association, but it can be made. They — books — led me to the place where I was to meet my wife … No, I don’t think the expression ‘ex-wife’ is more appropriate. It’s true that we live far apart, but on paper we’re still married. From a legal point of view, it was the best way our lawyers could find for me to continue to avail myself of a share of my father’s fortune, which is now limited to the payment of my monthly fees here. As I’m sure you know, I lost all right to any direct inheritance when I murdered him.

I can, therefore, call her my wife. And I will do so until the end of my days.

–17–

It was in Paris. I’d finished a degree in philosophy, and bought a place in a Master’s program at one of the best universities in France — not only to broaden my horizons, but also to get even further away from my father. He now liked to get his kicks speculating about my future as an unemployed philosopher who was — and this was even funnier, in his opinion — dependent on a capitalist pig who was making fabulous profits in the financial markets. My father was never very original in his jokes, like most capitalist pigs who make fabulous profits in the financial markets. And I, an unemployed philosopher without a future and the son of a capitalist pig, was annoyed by his hackneyed jokes. Anyway, this dependence was easier for me to swallow from a distance of ten thousand kilometres.

Since I was receiving a hefty allowance, I’d rented a flat at a fashionable address on the Left Bank, near the Musée d’Orsay. I attended university in the mornings, and had my afternoons and evenings free. To keep up with the course, all one had to do was read the books on the compulsory reading list, which wasn’t too extensive, and that was it. This business of Masters’ studies in France is a piece of cake. In my free time, I went to the National Library, where I caught up on French and Russian literature. Their translations of Russian authors are good, except for a few cosmetic interventions to polish up passages that must have been rather dusty.

Once a week, I went out to dinner with my aunt and her husband, who were based in Paris at the time. I’d already been living the good life for about three months when, one winter afternoon, I was approached by the woman who was to become my wife. I was enjoying an essay on Dostoyevsky, when I heard a husky voice — of a promising huskiness — behind me. ‘Such concentration!’ I turned around, irritated by my fellow-countrywoman’s bad manners. But instead of saying something impertinent, I froze.

The Day I Killed My Father

The Day I Killed My Father