- Home

- Mario Sabino

The Day I Killed My Father Page 2

The Day I Killed My Father Read online

Page 2

–5–

Yes, my father’s purpose in life was also to torture me. He never beat me, but he liked simulating fights so he could hurt me. His favourite method was asphyxiation. He’d immobilise me with the weight of his body and only get off when my face started going purple. To make me ‘a man’, he’d get me into an arm lock and wait until I begged him to stop. Once he broke my finger, which was only diagnosed two days later because he kept insisting that it was nothing and that I was being a ‘pansy’. My mother thought it was all normal. ‘Boys’ games,’ she’d say. But nothing hurt me as much as the three words he fired at me one night.

As you know, it’s common for children to wonder, at some stage, if they really did come from their parents. This adoption fantasy haunts boys and girls alike, and they will often try to assure themselves of their family identity. In my case, I did it indirectly by asking questions about the circumstances of my birth. I bombarded my mother with questions about the day I was born, the hospital she’d had me in, her first impressions of me — things like that. I also liked to see photos of myself as a baby. This all reassured me, but not enough to erase my doubts. And, whenever I could, I’d trot out my questions again.

It was after one of these question-and-answer sessions that my father decided to make his move. ‘Let me tuck him in,’ he said to my mother as he picked me up. When we got to the bedroom, he put me in bed, covered me, and sat down next to me. He stared at me for a few seconds and then, without moving a single muscle in his face, said, ‘You are adopted.’

I cried all night long until I heard the first sounds of the morning lashing at the window. My anguish manifested as an asymptomatic fever that increased at nightfall. Without a clear diagnosis, the doctor said I’d caught a virus. My mother tried to comfort me, but I fled her embrace. I came up with excuses and took refuge in my bedroom. I felt betrayed by her. Why hadn’t she told me? There was, however, an underlying question, which was impossible for me to formulate at that point: what to do with my love for that woman who was no longer my mother? I could, of course, have asked her if it was true that I wasn’t her son. Why didn’t I? It was out of resentment (I felt betrayed, as I said), but also for fear of what she might say. I think I was afraid I’d die if I heard her say, ‘It’s true you’re not my son.’

Any other father would have taken pity on me. But not him. On the contrary, he took the opportunity to gloat. At the dinner table, he turned my game around. He provoked me with general-knowledge questions, which I didn’t answer. ‘Now, now, someone’s got the smart-aleck’s tongue,’ he taunted. My mother begged him to let me be, to which he replied that he was only joking, trying to cheer me up. At one such meal, in the middle of one of his little performances, he said to my mother, ‘Can’t you see he’s acting all la-di-da? Come on, spit it out. What’s the capital of Hungary — Bucharest or Budapest?’ Angrily, I answered, ‘Budapest, you idiot. You’d know if you’d read The Paul Street Boys. But you don’t read anything. Only Mummy does.’ For my pains, I got a glass of water in my face. ‘Get out of here before I give you a whipping,’ roared my father, while my mother cried, mortified. That same night, my father came into my room and, after lecturing me on the respect that children owe their parents, started to tell me the tale of my adoption. ‘The only reason I’m not going to punish you is because I understand how you’re feeling about the adoption. You haven’t asked for any details, but I’m going to tell you anyway. You’re actually the child of a domestic we had the first year we were married. She asked us to look after you for a while, until she got back from holidays, but she never showed up again. She still might come back. But don’t worry. Mummy and daddy won’t let you go. Goodnight. Sweet dreams, son.’

Can you imagine my terror? No, you can’t. No one can.

My anguish lasted about a week. One morning, my father and I were sitting at the breakfast table when, without lifting his eyes from the paper, he said, ‘It’s interesting how living together can make people alike. Even physically. You, for example, have her eyes. Your mother’s. Your eyes are the same; everyone says so. When you were a baby there was no similarity.’ He folded the paper, placed it on the table, took a sip of coffee, and only then, after all those gestures, did he look at me. ‘We’d best keep this adoption story between us. A father–son thing. A man’s thing. Your mother wouldn’t understand. It’s part of the training you need to learn to deal with life’s difficulties. Come here and let me give you a hug.’

My eyes were my mother’s; I was no longer in doubt. My eyes …

He’d said that living together made people alike. But he’d also referred to the time when I was a tiny baby. Most adopted children are adopted when they are very small, I know, but that phrase — ‘When you were a baby’ — made me feel certain that I was their natural child and not adopted. It’s still a fragile certainty, even though I have become very much like my mother. Could this be through having lived together? But I didn’t live with her for very long, when all’s said and done …

I let my father hug me, in a mixture of relief and rage, without asking what had led him to torture me like that. It wasn’t necessary. It was already clear to me that we were enemies. After the relief and rage came a feeling that could be defined as gratitude. I was grateful to my father for having put an end to my agony, even with all his ambiguity. There’s an explanation for this: those who are tortured also feel gratitude toward their torturers when they stop maltreating them.

–6–

My tenth birthday party — a big one, which was going to be held at an amusement park — had to be cancelled at the last minute because my mother learned she had cancer. She would be dead in four months. The tumour had started in an ovary, and had spread to her intestine, stomach, and lungs. What have I got to say about it? Well, when she explained her illness to me, she didn’t tell me she might die. And, although I watched her waste away, it didn’t seem possible that she was about to disappear. She was hospitalised for the last time one morning after vomiting up a smelly, black soup that doctors refer to as faecal matter — the cancer had grown so big that it was blocking her intestine. When she left home, propped up by my father, she said, ‘Be happy, son.’ And she kissed me on the forehead, a cold kiss. I never saw her alive again.

I was woken in the middle of the night by my aunt, who’d come from abroad to help look after my mother, her younger sister. ‘Darling, I need to tell you something,’ she murmured. ‘What?’ I asked sleepily. ‘Your mother’s gone to heaven,’ she answered, her voice faltering.

At that moment, the words ‘Your mother’s gone to heaven’ made no sense at all to me. That’s why it took me a while to work out what had happened. When she saw my confounded expression (that was how she described it years later), she used the right words: ‘Your mother’s dead.’

I’m tired.

–7–

I’d like to go back a bit to talk about the effect that my mother’s wasting away had on me. Her gauntness, her listless gaze, her white skin, with the pallidness that announces death, her baldness caused by the chemotherapy — to me, this all seemed like a costume that could be taken off at any moment by the woman I loved so much and who seemed so strong to me. It was as if she remained untouched behind that emaciated body. While waiting for my real mother to come back, I avoided the sorry creature who dragged herself through the house and no longer sought my affection. It’s strange, I know, that a son as loving as I was could have behaved like that during his mother’s illness. But I had no idea she might die, and the fact that she didn’t look the same as always left me more perplexed than sad.

It was only that night that sadness caught up with me — or, rather, that I caught up with sadness, because maybe it was me who was behind it. But it was hard to separate sadness from remorse, and my pain grew because I was unable to do so. Why hadn’t I hugged her more? Why hadn’t I said anything the last time I saw her? I felt like I

was the cause of her cancer. In fact, more than that — that I was the cancer. I pulled away from my aunt, who was trying to hug me, and ran to my mother’s bed. I wanted to smell her, like little animals do when they look for their mothers who’ve gone forever … No, that image didn’t just come to me now. I’m faithfully reproducing everything that went through my child-mind. At that moment, I remembered the documentaries about baby animals I liked to watch on TV. I always got teary-eyed when I saw them abandoned. If I could find my mother’s smell maybe I’d be able to cry. But the tears didn’t come. They never came again. I don’t remember the last time I cried. I don’t know if it was because I was upset, hurt, or had been told off. All I know is that, after I turned ten and everything changed at home because of my mother’s illness, I never shed another tear.

With my face buried in her pillow, tearless, I broke into a cold sweat. Then I felt faint. ‘I feel dizzy, Aunty,’ I said. And at the wake, still reeling, I saw my mother’s face — wearing that stupid, beatific smile drawn on by those who prepare the dead — for the last time. Reeling, I watched as her coffin was buried and, reeling, I was patted by people I knew and people I didn’t. Still reeling, I glared at my father when he said, ‘Now it’s just me and you.’

I beg your pardon? Do I still have dizzy spells? Well, in my current state, it’s hard to say what I’m feeling. Sometimes I feel as if I’m being swallowed by darkness, while at others it’s as if I’ve lost my individual contours. What do I mean by that? I’ll try to explain. Let me see … It’s as if the sounds around me were passing through me. They enter through my pores, pass through my body, and carry away what I guess you could call my essence. I feel disoriented, but it’s not exactly dizziness or faintness. It’s a bit like the feeling described by people who have panic attacks when they find themselves in a crowd. Your body loses its limits, your very substance starts to wane, and it seems like everything is going to melt away, dissolve. To recover, I have to be alone, in complete silence, which isn’t easy around here with so many people coming and going from my cell all day long. From my room, I mean.

No, I didn’t feel dizzy when I killed my father. Nor did I feel at all faint afterwards. My lawyers said it would have weighed in my favour during the trial; to reinforce what they claimed was a temporary loss of lucidity or some such legal baloney. But I didn’t want to lie. At any rate, they managed to do a good job of convincing the different judges along the way that I should be locked up in a place like this rather than a prison. Though I helped quite a lot in that respect, too.

‘Now it’s just me and you.’ Yes, you’re right, these are words that precede duels in films. Except that there was never a component of fiction in our clash. It was the most real thing in my life. Now there’s nothing that can be done. And perhaps there’s nothing more to say either … I’m tired. My conversations with you every other day wear me out. I think it’d be better if we stopped them … What? That would put you in an awkward situation? Why should I be considerate with you? I don’t really know you. I only know your name — your first name. I don’t know where you live, if you’re married, if you have kids, if you go to a gym, if you suffer for any reason, how much you earn. Nothing. But you know everything about me — or you think you do. But I don’t tell you everything. Not even the file you had access to is complete. No, that’s also my tragedy: everything about me is known. I’m a man picked to pieces by analyses, descriptions, comments, judgements. There isn’t a soul alive with a more transparent background than mine. Actually, if you have a copy of my hefty court records, you don’t really need to be here, hearing it all again … Yes, that’s true, I must admit. As I retell my story, new details emerge. There’s one thing that bothers me, though. In spite of all the visibility that my existence has acquired, a part of me remains invisible, obscure, closed up inside itself. Is this what they refer to as soul — the essence that cannot be unravelled, no matter how closely we scrutinise it?

You read that I was writing a book when I killed my father. It’s true. I have an unfinished novel on my résumé. I’ve managed to keep it out of the hands of the law. It does have autobiographical elements, obviously, but nothing about my conflict with my father … You’d like to read it? I don’t know … The title? Future … What’s it about? A guy who’s lost, who’d like to make something of himself, and runs into insurmountable obstacles … What do you mean, ‘Is that all?’ Don’t you think it’s enough? My character has philosophical questions, which lead him to choose a certain path. Am I making you curious? I’m afraid you’re going to be even more disappointed in me if you read what I wrote. I wouldn’t like you to be disappointed in me, you know. I really like your voice, although I don’t hear it much … I’m sorry. I don’t mean to embarrass you. So, do you really want to read my book? We’ll see … But, if I say yes, you’ll have to agree to one condition — that you will read my book here, aloud, so I can hear it. It’d be an interesting experience for me to hear my words coming from your mouth … Do you agree to this? I’ll consider your request.

–8–

I decided to write a book because I was jam-coloured. That was the underlying reason. Before you ask, I’ll explain: when I was seventeen, that was how a literature teacher defined me. Jam-coloured. He considered himself to be a bit of a psychic, and liked to categorise people by colour. This game made him popular among the students — especially the boys, whom he appreciated from afar, as an inmate would, poor thing. He’d stare at a student in the face and, after a few seconds, as if he’d seen their soul, would tell them if they were blue, red, yellow, or green. As far as I know, I was the only one to be defined as jam-coloured. He stared at me a little longer than usual, hesitated, then finally delivered his verdict. I was intrigued, and asked him what jam-coloured actually meant, since jam came in a range of colours. He didn’t know how to answer.

Are you laughing? Go ahead … After so many years, it’s just funny. But I didn’t find it remotely funny at the time. To be honest, I still don’t find my teacher’s description funny. When you’re seventeen, you want, above all, to have clear contours, a well-defined colour. And jam-coloured isn’t any real colour; it’s nothing. It’s somewhere between burgundy and brown, I think … At any rate, my teacher wasn’t exactly wrong. I really was colourless, and remained so until I killed my father, when I finally gained a colour.

What colour is a patricide? It took me a long time to answer that question. But I did. A patricide is white, all white — the white of the nothing that once was everything. You don’t get it? Let me see … The white of a star that is born, develops, sparks the appearance of a system around it and dies in an explosion that swallows everything around it, and is quickly followed by an incredible concentration of matter that is no longer anything. Just a white spot in space. Colours … Even my nightmares used to be in colour. With time, black and white took over my dreams, colours became memory — and, from memory, they turned into concepts. The concept of red, the concept of green, the concept of yellow. And the concept of white.

Might I also lose these concepts one day?

As I was saying, I decided to write a book because this undefinable jam colour impregnated my existence until I was an adult. It extended into every corner of my life. My jam-coloured existence was almost completely unreal, and I urgently needed to become real — or to belong to a reality, that is, that bore no connection to that of my perpetual war with my father. It’s curious that one might turn to fiction to reach reality, but I think that’s how it works for some writers or would-be writers — and I ended up becoming just that, a would-be writer. Many years ago, I watched a re-run of an interview with Clarice Lispector [the Brazilian writer who lived from 1925 to 1977]. Have you read Clarice Lispector? What a silly question; of course you’ve read Clarice … How do I know, if you didn’t answer? Something about the way you speak makes me assume so.

She’s not my favourite writer, but I was quite taken by her persona. T

hose almond-shaped eyes that seemed to see an invisible world, her crooked fingers, her strange accent with inflections from the Brazilian north-east and the Ukraine. Clarice, in all her humanity, was an other-worldly creature. Anyway, in this TV re-run, at a certain point she said she wrote so as not to die; it was what kept her alive. And between the end of one book and the beginning of the next, she died. That sense of death, uselessness, lack of horizon, disorientation, was what I was feeling at the time, regardless of the fact that I was dutifully completing each stage of life that a man is supposed to. The end of my university years, finishing my Master’s in France, moving into a home of my own, getting married — nothing had jolted me out of this frame of mind. My anxiety was like a noise. Sometimes louder, sometimes quieter, sometimes almost imperceptible, but always there, present. After watching the interview with Clarice, I thought that maybe during the writing of a book I’d be able to put it — my anxiety, I mean — on hold. If it all worked out, I could write books back-to-back, and thereby go on living with some pleasure.

Obviously I’d already thought about being a writer before watching the interview. But it was important in helping me decide to shake off my state of lethargy. A brainwave? Yes, a brainwave. I was teaching a few classes at a shoddy university, doing the odd translation, proofing the occasional thesis — so I had plenty of spare time to devote to writing a novel. But I always ended up finding a way to put off sitting down at the computer. I still didn’t have enough incentive to turn my paralysing anxiety into stimulating anxiety. Money? You know my father was rich. Every month he deposited a handsome sum into my bank account, which increased after I got married, seeing as my wife was what you might call high-maintenance, and my father admired her for it … Yes, being supported by my father was a source of some anxiety. I was just one more whore he paid … Sorry? I said at the beginning that he didn’t sleep with prostitutes? That’s true. But that’s how I felt — like a whore. Like everyone else who orbited around him.

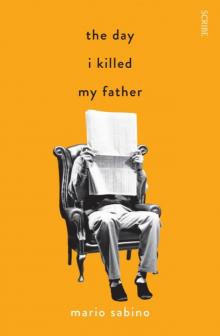

The Day I Killed My Father

The Day I Killed My Father