- Home

- Mario Sabino

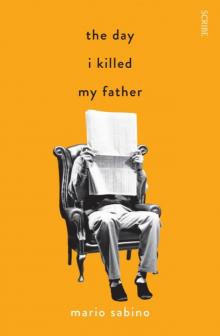

The Day I Killed My Father Page 3

The Day I Killed My Father Read online

Page 3

A few months before I saw the interview with Clarice, I started analysis. I admit that therapy also helped a lot in my decision to write. But maybe my analyst thought that my initiative was just a way of working through the neurosis of the … that complex … Why do I avoid talking about the Oedipus complex? Before everything happened, the only reason I didn’t mention it was because the name sounded ridiculous to my ears. Perhaps because I’d heard conversations in which people came out with things like ‘My Oedipus is affecting my relationship’ or ‘Your Oedipus is stopping you making the right decisions’, with embarrassing ease. After I killed my father … Well, let’s just say I’m over him in such a way (not in a psychological sense, obviously) that an Oedipus complex alone cannot begin to describe my tragedy. It has become too weak an expression. Actually, have you ever noticed how words and concepts are only accurate when defining what happens to other people, never ourselves? Or is this just the impression of one who considers himself superior to others, better than everyone else, even when misfortune befalls him? Did you know my analyst wrote that my narcissism was so monstrous that in order to differentiate myself from mere mortals, I’d decided to brand my own story with the myth, becoming it myself. It seems quite plausible; even so, after that interpretation I can’t help but think of her as a fucking bitch.

–9–

For two years after my mother’s death, I went to mass every Sunday. I was taken by an old domestic of ours who thought it was my duty, as an orphan, to pray to God for my mother’s soul. The architecture of this church was curious. It was simple outside; imposing inside. It had a main nave and two side aisles. The columns separating them were made of dark marble, with fine Corinthian capitals. The high-altar scenography involved a statue of Jesus on the Cross, with statues of Mary and Mary Magdalene on either side, kneeling, gazing at him. Behind them, a purple curtain, like the ones in opera theatres, provided the backdrop. Above the high altar was a fresco of the Resurrection: Jesus, holding a standard with a cross on it, was levitating over the tomb that had held his body, while Roman soldiers shielded their eyes against the light emanating from the divine spectacle. Next to the high altar was a huge pulpit carved in dark wood, where the priest preached. Opposite it, above the main entrance, was a silver organ, which was only used on special occasions. The side aisles had chapels devoted to different saints, most of whom were Italian, since the church had been financed by Italian immigrants. The altar in the left-hand aisle had a statue of Saint Paul of the Cross, while the right-hand one had a statue of the Virgin Mary.

It was in this church that I had taken my first communion and shat my pants during a school ceremony, the shit seeping through the white knee-highs that were part of my school uniform. Both occasions were branded in my memory, not least for the fact that my father wasn’t present at either one. On my first communion, arguing that it was just institutionalised superstition, he spent the day out of town on a friend’s farm. My mother was really hurt, but I liked not having him around. I managed to be the centre of attention all day long. As for the school ceremony, I don’t remember why he wasn’t there. I was relieved he hadn’t witnessed my public humiliation — and my mother didn’t tell him anything about it, on my insistence … You think she might have told him without me knowing about it? I doubt it. He would have mocked me. If he didn’t, it’s because he didn’t know.

This old domestic of ours liked to go to church on Sundays because it was an opportunity for her to have some kind of social life. Not that there wasn’t any religious sincerity in her habit. There was, and lots of it, as demonstrated by the fervour of her prayers and her room full of pictures of saints. But she didn’t hide her happiness at being able to chat with her equals — the absence of which she resented in our oh-so-hierarchical home full of employees who were always being replaced by my father. For this reason, we always arrived at church half an hour early. I took these moments to wander through the church alone, stopping at the chapels with the most shocking paintings and statues. The one that most fascinated me was a statue of Christ dead, lying inside a glass urn. It was in the first chapel of the right-hand aisle, and was always the final destination of my solitary wanderings. The statue only left there when it was carried by the faithful in the Good Friday procession, thereby making the gloomy streets around the church even sadder. I’ve never seen one of these processions — my father wouldn’t allow it — but our domestic’s descriptions were so vivid that, in my mind, the scenes took on the contours of something I’d actually witnessed. It’s as if I’d personally watched the slow steps of the hooded men in white tunics who carried the dead Christ, and the men who lit the way with torches, and the women who chanted the Lord’s Prayer in a lament that could be heard on the top floors of the buildings, although there weren’t as many buildings in the neighbourhood back then. I wonder if the procession still takes place. Do you think you could find out for me? Never mind …

The dead Christ statue seduced and terrified me, like a lover who inspires both attraction and repulsion. Alone, standing before the glass urn, I tried to look away, but it was useless. The stigmata on his feet and hands, the blood running from his chest and head wounds, the crown of thorns that still hurt him — all these details mesmerised me. Nothing in the church seemed as alive as that dead Christ, if you will allow me this paradox. I only turned away from the statue when the small bell that announced the start of mass was rung. No, I’m mistaken. I only left when I saw the priests going into the wooden confessionals that stood between the chapels. I liked confessing, so I could take communion afterwards. My sins were always the same four: disobedience, insolence, recalcitrance, and swear words. I was, in fact, obedient, polite, and helpful, and almost never swore. But you had to have sins in order to confess them and then get the communion wafer. Kneeling in the confessional, I’d murmur my sins to the priest, who would absolve me and prescribe my penance: five Our Fathers, five Hail Marys, and three Acts of Contrition. The accounting was always the same for my four sins.

When I left the confessional, I’d head to the pew where our domestic was sitting, kneel next to her, and pray with great concentration. I’d say, ‘Forgive me, God, forgive me,’ between each of the prescribed prayers and after the mea culpa. After receiving the wafer in the communion ceremony in the last third of mass, I’d go back, kneel again, and say an Our Father and a Hail Mary for my and my mother’s souls. The domestic was always moved by the ardour with which I prayed — so much so that she even spoke to my father about the possibility of my becoming an altar boy. ‘The boy’s blessed,’ she said. My father didn’t answer, let out a sarcastic guffaw, and ordered her to make coffee. ‘I think it’s about time she moved on,’ he said aloud when he was alone with me in the living room.

Where am I going with this story? Well, I think it’s necessary in order for you to understand an important aspect of my unfinished book.

The Sunday before the poor domestic was fired, I made a discovery after mass was over. In fact, that was the last mass I ever attended in my life. It was also the last time I set foot in that church.

Before leaving, the domestic stopped for a quick chat with some acquaintances. Since I wasn’t even remotely interested in their conversation, I decided to take another spin through the side aisles of the church. The sound of my shoes made an echo, an effect I emphasised by stomping. Almost automatically, I ended my jaunt at the chapel that held the glass urn with the dead Christ. There was no one around — the group of women were at the entrance near the baptismal font. I was looking at Christ’s stigmata, when a thought popped into my head: It’s all a lie. But, if it were true, that loser would have deserved to die like this.

I started to shake, and broke into a cold sweat. Where had that thought come from, for God’s sake? Christ was a loser! A loser! The words were now hammering in my brain and, worse, threatening to leave my mouth. Desperate (yes, desperate is the most accurate definition of my state), I ran to the hi

gh altar, where there was the statue of the Virgin. I knelt before her, to say however many Hail Marys, Our Fathers, and Acts of Contrition were necessary to atone for my sin. But what happened was even worse. I gazed at the Virgin’s face and thought: This is the pro who bore that loser. And she must be the daughter of another pro, who was the daughter of another pro, who was the daughter of another pro, all the way back to the beginning.

I fled. I ran into a priest coming out of the sacristy. ‘What’s the matter, son?’ he asked, trying to stop me. I wiggled out of his grasp and headed for the entrance, where the domestic was. I tugged at her hand. ‘Let’s go! Let’s go!’ I cried. The terrible thoughts were still echoing in my head: Christ was a loser! The Virgin was a pro who was the daughter of another pro. When I got to the square in front of the church, I looked at the façade with its enormous cross and thought: I’m going to crap all over this bullshit.

–10–

The first time I ever mentioned this episode was many years later — talking to my analyst, of course. She interpreted it shrewdly, I must say: when I was cursing Christ, I was expressing my unconscious indignation at my own condition as a boy sacrificed by a father who oscillated between irascibility and absence. When I was cursing Mary (of the immaculate conception, no less), I was expressing my anger, also unconscious, at the mother who had abandoned me and who, at the same time, occupied my entire existence.

I wish I’d had an analyst at that moment in my life. Because, after what happened, I began to believe I was the Antichrist: the Beast that had come to destroy the world. At the same time, a part of me believed the opposite — that it was just a test of my infinite faith. And for this reason I prayed, and prayed, and prayed. I prayed every time the thoughts popped into my head, whether I was at home or in public. When they appeared in the presence of other people, I prayed in a way that they wouldn’t notice. I even developed a technique for making the sign of the Cross in slow motion, so to speak, so no one would catch on. Hail Mary always came after Our Father. I read the Hail Mary in Latin in an old missal I found among my mother’s belongings. I memorised it and started reciting it in Latin because it seemed more sublime and, therefore, more effective. ‘Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum, benedicta tu in mulieribus et benedictus fructus ventris tui, Iesus. Sancta Maria, Mater Dei, ora pro nobis, peccatoribus, nunc et in hora mortis nostrae, Amen.’

The anxiety instilled in me by the certainty that I was the Antichrist was to last quite a while. It dissipated slowly, and an important determinant in its erasure was finding out that the Romans used to curse God and the Virgin Mary. For me, the Roman blasphemies represented liberation. ‘Dio cane.’ ‘Porca Madonna.’ These expressions still sound like poetry to me. It was because of them that I started studying Italian.

Do I believe in God? I could quote Woody Allen: ‘To you, I’m an atheist; to God, I’m the Loyal Opposition.’ At any rate, knowing of my childhood religious experience is essential for you to be able to understand one of the main aspects of my unfinished book. I wanted to understand how Evil was born in our souls. Because that was my frightening discovery that day, as I later managed to articulate: I, a mere child, was already filled with incommensurable Evil.

My analyst’s explanations, I know. Shrewd, but partial. But they only explained the triggers for something that I believed (and still do) was pre-existent … Have I found an answer to my philosophical question? I have a few theories on the subject, but I’d rather leave them for later. There’s no rush. I’ve got plenty of time on my hands. Actually, it’s the only thing I have got.

–11–

Here’s the file containing Future. I’ve decided to bring forward the reading for three reasons. First, I miss my characters — yes, ‘miss’ is the right word. Second, I’m anxious to hear your opinion about the book. Isn’t it curious that I barely know you and that I already need your opinion? Last, I think Future will help you understand some of my processes. Just some, mind you.

The main condition for me to let you read it, I repeat, is that you do so aloud. I don’t think it should take more than four sessions to read. There are other conditions. You can’t take the file home. At the end of each session, I’m going to check the number of pages in it. Please excuse my lack of trust, but I wouldn’t like people I don’t know to have access to my book. Read slowly, please, and don’t try to give the characters different voices. I detest those kind of theatrics. Last of all, there are to be no comments during the reading. Nor do I want to hear your observations after each session. You’ll read it, then leave, in silence. We’ll only discuss it when you’ve got to the end of the book. Do we have an agreement?

It will be a pleasure to hear what I wrote coming from your mouth.

Future

(a novel)

I

When he read in the paper that light pressure applied to the earlobe could bring on a sudden heart attack, Antonym became suspicious of Bernadette. After all, it was a more subtle method than pouring molten lead into a victim’s ear. He saw the article — of dubious scientific quality — as a kind of confirmation. Not just of the motive behind some of his wife’s caresses, but also of the theory he’d been nurturing. One day, while waiting for the bathroom to be vacated, a strange matinal mosquito was droning at the entrance to his left ear. At any other time, Antonym would have merely grumbled and swatted the air. But at that hour of the day, when a healthy man has his batteries fully charged, the drone of the insect inspired a quick, though not unreasonable, formulation. After squishing the mosquito against the wall, Antonym realised that it was through their ears, rather than their eyes, that men were seduced. The ear canal connected a man’s body and spirit. Caress the eardrums of the most mediocre of beings with words of praise, and he will believe himself to be a wise man; nibble, even just slightly, the earlobe of a wise man, and he is reduced to nothing. Armed with this principle, one could even write, for example, an essay on the harmful aspects of constructive criticism. But Antonym would never do that. He would be caught up in ordinary events that would lead to the extraordinary.

It was nothing more ordinary than a marriage break-up. The relationship had lasted ten years, and would have lasted even longer had Bernadette not plucked up courage and decided to leave, after giving him a long and civilised explanation of her decision.

‘I need to be around normal people,’ she said in conclusion, before picking up her bags, which were already packed, and going to stay with a girlfriend from work.

The sterility of the scene made Antonym proud. His wife had perfected the ability to control noisy reactions.

‘Can I ask you one last thing?’ asked Antonym.

‘?’

‘Did you ever think of killing me?’

Bernadette got into the lift.

II

The change in Antonym’s marital life had an immediate effect on his work. He was unable to come up with enough witty ideas to maintain a good flow of opinionated articles, and his reporting became substandard — even for the third-rate newspaper he worked on, he was forced to admit. His lack of productivity allowed the editor to start detecting lumps in his velvety style, which up until then had been a source of pride for the editor, who believed he had ‘discovered the kid’. Whenever he heard him trot out this phrase, it struck Antonym that editors-in-chief were like pimps — always keen to find new talent. It was a shame that that was a cow he couldn’t milk any more.

‘An article in the first person, Antonym? That’s not done in contemporary journalism.’

‘Antonym, please go lighter on the “howevers”. Your texts are full of crutches.’

‘Listen, Antonym. Why don’t you use the first person? It’s more contemporary.’

‘A crutch wouldn’t be so bad here, Antonym.’

‘I think you should have some time off to reflect on life, Antonym. No hard feelings, OK?’

Antonym was out of the game. Since he’d made countless enemies on all the other newspapers and magazines, he wasn’t likely to find work again on a big publication.

Well, at least a lot of people will be happy now, he murmured to himself, as he closed his car window in the face of a kid begging for money. No self-indulgence, no indulging others. No hard feelings, OK? That was how he had to be.

In theory, it’s possible to love thy neighbour. But from a distance. Close up, it’s almost impossible. He remembered that this was what Bernadette had always said whenever she saw him cursing the vagrants that had taken over the city.

Before he went home, it occurred to him to call someone who could keep him company during his first dinner as an unemployed person. And it was only then, and not without some perplexity, that Antonym understood in reality (which is quite different to understanding in theory) that he had been isolated for years. He had delegated the job of making contact with the outside world to Bernadette, which had meant only going out with her friends and workmates. His own social life was restricted to his work, which gave the term ‘social life’ far too narrow a meaning. All he had left was enemies. But even they were distant rather than close. Because there were bosom enemies (with whom one could seek reconciliation any time, given the fact that they used to be friends before the fight that caused the falling out), and there were distant enemies. With these, the confrontation generally took place before there could be any kind of friendly exchange or recognition of like-mindedness. Underpinning them might be a quick comment to a third party, a funny look, or a difference of opinion of little relevance on an equally unimportant subject. Since the animosity was established right at the outset, distant enemies were eternal. You couldn’t reunite what had never been united.

The Day I Killed My Father

The Day I Killed My Father