- Home

- Mario Sabino

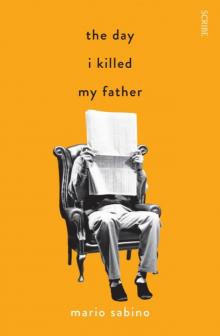

The Day I Killed My Father Page 6

The Day I Killed My Father Read online

Page 6

‘But when we met outside the bank he showed an enthusiasm that I can only describe as inexplicable. For my part, I pretended to be happy to see him after so many years, asking questions whose answers I wasn’t even remotely interested in. My act was so convincing that he invited me to dinner that Saturday, in a restaurant that had recently opened. Since I was single, he wanted to introduce me to a friend of his wife’s. The four of us could go out together; what did I think? At best, I didn’t think anything. At worst, it was a fucking stupid idea. I fought the instinct to choose the path dictated by the second response. I accepted the invitation. Pleased I’d agreed, he gave me a hug (a rich man’s hug, emanating a slight trace of musk), and added that it was about time we rekindled our friendship. I not only agreed, but I also lied and said I’d thought about trying to track him down recently. He said that we’d have plenty of opportunities to make up for lost time. I got his card; he jotted down my number. Our arrangements included a whisky at his place before dinner at the restaurant. When he got into his flashy car, surrounded by security guards, I sighed with regret. But there was no turning back. I had a date for the next day.

‘At the agreed time, I arrived at my former classmate’s home. The couple’s friend was very attractive. She was about thirty-four, with a little body, tight from working out, and accentuated by a low-cut dress with slits up the sides.’

‘Thirty-four …’

‘What about it?’

‘I love women about that age. They’re still spring-like, but starting to show signs of the autumn to come.’

‘Your images have been better.’

‘I know. It’s no accident I’m up shit creek.’

‘Anyway, there was this gorgeous woman. She was friendly, and said she enjoyed reading my reviews and had bought the little book I’d written on twentieth-century Italian poetry (in which, incidentally, I used many of your observations, Antonym). Then she told me that she was married to a powerful senator, who was abroad at the time. Before we left for dinner, she and my friend’s wife went to the bathroom to touch up their makeup — at least, that was their excuse. My friend took advantage of their absence to ask me straight up if I was interested in the senator’s wife. I said I was. He told me that I should feel free to make a move. The senator wasn’t too partial to sex, and his constant travels allowed his wife to have sexual escapades. He himself had already “served the nation”, he revealed with a wink.

‘When they came back from the bathroom, we had another dose of whisky, which had the effect of freeing the woman and me of any inhibition. Sitting in the back seat of the car, I ran my hand over her thighs, while she gently massaged my dormant penis. At the entrance to the restaurant, she patted my arse. My friend’s wife must have seen this because she whispered something in his ear that made him chuckle. All very vulgar.

‘In the restaurant, the petting continued under the table. I felt light, and so carefree that I hardly spoke during dinner. Since my thoughts were disposable anyway, I focused on the food being served. And focusing on one’s food means to chew it slowly and to gently wet it with one’s saliva in order to excite the most insignificant taste buds — all those things that are barely contained by the verb “to savour”.

‘Somewhere between the salad and the main course (a magnificent pasta sprinkled with white Piedmont truffles), behold, I began to see the world with a clarity I can only call supreme. How much time I had wasted, for God’s sake! Everything was so close, so simple … With each forkful, my clots of unhappiness dissolved and my blood flowed, expelling my torpor. I was being reborn from the mildew of my inflated self-image — and in my true size. My search ended there where my little “big truth” had begun — in the fleeting happiness that had washed over me during dinner. Through my palate, I had recovered my senses in a pure state. I was reliving the childhood of man, not as a regression, but as a triumph. I was about to embark on a new story: my own.’

‘I know — it was the white Piedmont truffles.’

‘Maybe one day you’ll reach the dimension I’m talking about, Antonym.’

‘It’s just that I find it funny that you had an epiphany (can I call it that?) while dining with a slut.’

‘It is this banality — or vulgarity, if you like — that makes this particular fact all the more relevant. It was at this moment that I decided to open my own restaurant; a restaurant different from all others. Actually, the word “restaurant”, or “steakhouse”, doesn’t really express my intention to build a temple dedicated to satisfying the senses.’

‘The blackmail …’

‘That evening, I recovered my potency with the senator’s wife. We fucked four times that night, and to this day I get horny just remembering that shameless little whore’s screams. The next day, my friend called me. From his insistence that I describe the most obscene details, I gathered he was a voyeur. I was right. He confessed his perversion, which was shared by his wife, and proposed that we secretly videotape me having sex with his wife’s friend. The equipment would be installed in a flat that he’d lend me for our dates. I agreed.

‘My friend, however, never got his hands on the tapes. I used them to blackmail the limp senator and his nymphomaniac wife. I also got a nice sum from my rich friend, who didn’t want to be publicly known as a voyeur. When I got death threats from them, I told them that copies of the tapes, along with a letter in which I accused them of my murder, were in the hands of a friend who lived abroad. To be honest, the friend lives here. Anyway, to cut a long story short, I came out of it all with more than enough money to set up my own restaurant.’

‘A temple in honour of anti-intellectualism, and built on sin.’

‘My anti-intellectualism, Antonym, if it can be called that, is the fruit of one who used to entertain intellectual ambitions and then realised how much they can hold you back from life. Don’t mistake it, please, for an apology for human idiocy. As for sin, well … That, too, is God’s work.’

‘How curious … Do you know Farfarello?’

‘The priest? Of course I do.’

‘ “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the intelligence of the intelligent I will reject. Where is the wise man? Where is the scholar?’ ’’

‘I have to admit that it was actually Farfarello’s idea to put that biblical quote over the entrance. But I haven’t seen him for a while.’

VIII

Antonym hoped a good night’s sleep would be enough to erase the feeling of delirium brought on by the dinner at Hemistich’s restaurant. But it only made it grow. It hadn’t been a dinner, but a ritual in which he’d unintentionally taken part. Why had Hemistich invited him? To persuade him to swell the ranks of his Christian hedonism? The expression ‘Christian hedonism’, an apparent paradox, had come into his mind because it had been the subject of an interview he’d done some two years earlier with a historian of religion who’d written a book about it. The only reason Antonym had been chosen to interview him was that he’d studied at a Catholic school. The result had been a mess but, luckily for Antonym, no one read the cultural section of the Sunday paper.

From what he could remember, this so-called ‘Christian hedonism’ was based on simple logic: if it is God’s will that all men be happy, and it is natural that men want to satisfy Him, the most logical thing to do is to make the most of the sensorial experiences provided by the Creator. Could Hemistich, therefore, be defined as a Christian hedonist? Antonym decided he couldn’t. This was because both the tenets and the consequences of hedonism, whether Greek or Christian, were moral — and there certainly wasn’t any morality in Hemistich’s deeds, discourse, or sensorial orgies.

In fact, the very idea that Hemistich had become religious struck him as absurd. He remembered that he only used to make reference to God, pretending to believe in Him, to impress those girls who made the sign of the Cross when they passed in front of a church. �

��It’s worth it; they’re the hottest ones,’ the sleaze used to say. As Antonym had already witnessed, Hemistich spoke about religion in a way that sounded highly original to the girls. Between one glass of wine and another, he borrowed from Pascal’s Wager, using the sophism born of the seventeenth-century French philosopher’s fertile imagination. While the lass he wanted to bed looked on questioningly, Hemistich would explain that, in order to rationally prove the existence of God, Blaise Pascal had argued that, from the point of view of mathematical probability, not to mention pragmatism and voluntarism, it didn’t make sense to believe He didn’t exist.

‘The argument goes like this, my dear: if you believe God exists and it turns out to be true, you’ll be rewarded with salvation, glory, eternal life and whatever else. If you believe God exists, but it turns out He doesn’t, you don’t lose anything for having believed. The opposite, however, offers no advantage: if you believe God doesn’t exist and it turns out He does, all you have to look forward to is damnation and misery. If you believe God doesn’t exist and He doesn’t, you don’t lose anything for having been a sceptic. It thus makes more sense to believe in God seeing that, in the best-case scenario, one has everything to gain and, in the worst, won’t suffer because of it. To us, my gorgeous. Cheers.’

The girls who made the sign of the Cross when they passed in front of a church were enchanted by Hemistich Pascal’s words — and started to believe in the existence of his feelings when they had much more to gain by not believing.

No, Hemistich hadn’t changed. He was the same bullshit artist as always, although he claimed the opposite. But what about his friendship with Farfarello? Perhaps ‘friendship’ was too strong a word. Nevertheless, the priest had suggested that Hemistich place the biblical quote over the restaurant door — and there was that line about God creating sin, which Hemistich had uttered as if it were an echo of something he’d heard with his own ears from Farfarello’s mouth … Everything suggested an intimacy that went beyond mere acquaintance. The priest’s spiel about Hegel — the Idea, great men — didn’t fit … Or did it? Antonym had asked Hemistich how he knew Farfarello, but he’d avoided the question. ‘I’m late for an appointment,’ he’d said, quickly excusing himself. It was some coincidence that he’d run into Farfarello shortly before the dinner at the steakhouse. Coincidence … Was it really a coincidence? Now, that would be really silly: believing in Destiny with a capital ‘D.’

Antonym was confused.

IX

‘You forgot this.’

‘Funny, I thought The Brothers Karamazov was yours. Our things got so mixed up over the last ten years that I … Thanks.’

‘I have to admit, I only finished reading it last week. I’d never managed to get past the first forty pages.’

‘I always suspected you hadn’t read everything you said you had. Journalists … ’

‘Anyway, I don’t mean to impose … ’

‘Want a coffee?’

‘OK.’

He followed Bernadette into the kitchen. She’d made a nest all her own, in which he recognised objects that were once part of the scenario of their life together.

‘These things that used to be in our home and now are here … They’re like debris from a shipwreck washed up on a quiet beach.’

‘That’s what they are: debris from a shipwreck. You’re still good at coming up with images. Aren’t you going to write any more?’

‘I’m helping a guy on an in-house newspaper.’

‘Is that enough?’

‘To get by, it is. From a financial point of view, I mean.’

‘What about from other points of view?’

‘I don’t have other points of view any more. Even the financial one’s hard enough to maintain.’

‘You seem pretty depressed.’

‘What did you expect?’

‘That you’d get better after we broke up. When you were with me, you always seemed so unhappy.’

‘You always wanted a big house with a garden and a dog … and this flat’s so …

‘So small. But who said I’ve given up my dreams? This is just my launch pad.’

‘You never were good at images. Are you still at the bureau?’

‘I am, but I’m getting ready to open my own office. I’ve rented a place with a partner.’

‘A partner. Right. What’s his name?’

‘It doesn’t matter. You don’t know him.’

‘Let’s see if I don’t know him … Is he …?’

‘Coffee’s ready.’

‘You cheated on me.’

‘Antonym, please don’t make things any more difficult.’

‘You cheated.’

‘It’s a woman, Antonym.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘…’

‘It’s a guy. You’re a terrible liar.’

‘Get a detective to follow me. Aren’t you going to drink your coffee?’

‘I’ve got plans, too, you know.’

‘Great.’

‘Hemistich wants me to go into business with him.’

‘To be a partner in that restaurant of his?’

‘I’m not exactly sure. To be honest, he only said he wants me to work with him. We’re going to discuss it a little further down the track.’

‘I went to Hemistich’s restaurant a while back. I didn’t think it was anything special.’

‘That’s because you didn’t go to what he calls a “closed-door event”.’

‘What’s a closed-door event?’

‘A special dinner he throws once a week. I’m always invited.’

‘Is the food any different?’

‘The food, the drinks, the people; everything is different from normal. These events are a real epiphany. I’m completely hooked now. When I’m there I have really intense, incredible feelings. I think I even have visions.’

‘Visions? And here I was, thinking you’d stop at paranoia … You thought I wanted to kill you, remember? By pouring lead into your ear while you were asleep.’

‘That was just a fantasy, Bernadette, which I never should have mentioned. But these visions … Those paintings of fauns and nymphs that come to life and skip down from the walls.’

‘I didn’t see any paintings of fauns or nymphs on the walls.’

‘That decor’s only used for special events; it’s the same with the bullfights in the bar and the biblical quote at the door. Hemistich has spent a fortune installing moveable panels and walls and other contraptions. Curious, isn’t it?’

‘Indeed. It sounds like the normal restaurant’s just a façade for these events.’

‘Doesn’t it?’

‘…’

‘…’

‘Your coffee’s waiting. One-and-a-half spoonfuls of sugar — is that still right?’

‘Yes. Bernadette, do you … No, forget it …’

‘What?’

‘Bernadette, you believe in God. Do you think Evil is an integral part of His nature?’

‘What?’

‘Just answer …’

‘It’s strange you should ask me that.’

‘Why?’

‘You, who’s always said religion should be classed as fantasy fiction.’

‘That’s actually an adaptation. Someone once said that metaphysics should be considered fantasy fiction.’

‘Have you become religious?’

‘Let’s just say I’m tinkering with the subject. Come on, answer my question.’

‘Isn’t it God’s will that even the innocent — including children — suffer in order to fulfil his plan?’

‘Ivan Karamazov.’

‘Yes. That’s about as far as I can get.’

‘Some sch

olars say Dostoyevsky meant that God exists because evil and pain exist. If the world were good, in essence, God wouldn’t be necessary. From this point of view, therefore, I think one can say that Evil is an integral part not only of the divine plan, but also of His nature; God’s nature.’

‘You needn’t have asked me anything.’

‘The day I was fired from the paper, I remembered something you used to say: “It’s impossible to love thy neighbour from up close,” and so on. That’s also Karamazov’s.’

‘I know. That’s about as far as I can get.’

‘I should have read more Dostoyevsky. There’s no method to my reading. I’ve got so many gaps because of it. Russian literature, German philosophy … I’ve wasted time reading a heap of useless Italian literature.’

‘To seduce mummy. Mamma Roma.’

‘Mum … Living with her was unbearable, but sometimes I miss her so much. As for Dad, I don’t know what to think …’

‘I was really fond of her, too …’

‘I know. And I’m jealous that you had your own relationship with my mother.’

‘Vitellone …’

‘Isn’t it funny how there’s still so much intimacy between us?’

‘Intimacy takes a while to die, but one day it does.’

‘Do you ever think about me?’

‘I do, and I quickly stop. The last few years of our marriage were really hard going.’

‘But we’re friends, aren’t we?’

The Day I Killed My Father

The Day I Killed My Father