- Home

- Mario Sabino

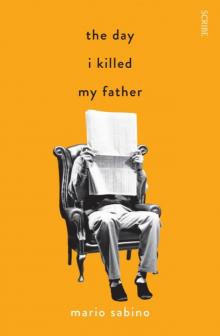

The Day I Killed My Father Page 7

The Day I Killed My Father Read online

Page 7

‘They still haven’t invented a category for the current stage of our relationship. I have friendly feelings for you, but we’re not friends. I miss you, but I don’t want to be with you. I remember our past, but I’d like to forget it. Maybe, with time, we’ll manage to become just ex-wife and ex-husband — the first step towards a mutual friendship — unless there’s some kind of major conflict along the way. Anyway, it’d be worse if we’d had a kid.’

‘You really wanted children … ’

‘I still do. You never did. You’ve always hated kids.’

‘I don’t hate kids. I just don’t want any competition. I was thinking, we could go on a photography safari in Kenya. It’s always been your dream. I know your dreams better than anyone does.’

‘Antonym, I didn’t want to tell you now, but you’d find out anyway, so it’s better you hear it from me.’

‘What?’

‘I’m pregnant.’

‘…’

‘Are you OK?’

‘No, I’m not.’

‘You look pale. I’ll get you a glass of water.’

‘I was right. You cheated on me.’

‘That’s crazy. We broke up almost ten months ago, and I’m only two months pregnant.’

‘I know you, Bernadette. You wouldn’t get pregnant to a man you’d only just met. Who’s this guy you’ve obviously been screwing for years — your partner?’

‘No, he’s not my partner and I haven’t been screwing him for years. The guy, as you say, is an ex-boyfriend from when I was a teenager. I ran into him again at a resort.’

‘At a resort! So, you hang around resorts now?’

‘Would it make any difference to you if it had been ... um, at the New York Plaza? I needed to unwind, and a friend suggested a resort. He also needed to get away from it all. He’d broken up with his wife a few months earlier …’

‘What a cock-and-bull story.’

‘To sum up the cock-and-bull story, there was an amazing dinner he’d arranged to have served at his bungalow: a dazzling full moon on the veranda, divine wine, and a really big, soft, nice-smelling bed.’

‘Spare me the sordid details. You forgot to mention the opportunistic bastard and the needy, irresponsible woman. What if he’s got AIDS?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Antonym. But if it makes you feel any better, I haven’t seen him since. He lives in another city. We spoke two or three times after that, always by phone, and that was it. The last time we spoke he told me he’d got back together with his wife.’

‘And you bawled your eyes out, obviously, feeling used and abandoned. What’s the bastard’s name?’

‘I can’t say I was happy about it, but it didn’t bother me that much either. To be honest, it helped reinforce my decision not to tell him anything.’

‘He should pay for the abortion. You’re going to have an abortion, of course. I’ll pay.’

‘I’m not having an abortion.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I want a kid now. I’m already thirty-five, and finding a man who would meet my long list of requirements would take too much time. Not to mention the fact that the odds of my search failing are greater than my odds of success.’

‘You’ve lost it …’

‘…’

‘I’d like this kid to be mine, Bernadette. Why don’t you have an abortion so we can have a baby of our own?’

‘This conversation ends here, Antonym. When you get your head screwed on right, we can talk again.’

‘You shouldn’t have done this to me. I need you, and now a foetus has come between us. You’re going to love this kid more than you ever loved me.’

‘You need help, Antonym.’

‘Not that psychologist crap again. You’re the one who’s sick, Bernadette. Who ever heard of having a kid like this?’

‘You know what, Antonym? Go fuck yourself. Since we split up, I’ve been making plans that have a chance of working out. I no longer suffer from paralysis — your paralysis. Your inaction, your boredom, your depression contaminated me for a decade. A decade! It’s what my analyst calls my “lost decade”. The best thing that’s happened in my life was breaking up with the sick person you’ve become. Your cynicism is the fruit of your frustration, your limitations — as a man, as a professional, as a human being. You’re cynical, Antonym, because you’re mediocre. And your cynicism is a comfortable way to hide this fact of life. I might not be anything special, Antonym, I might not know what I am, but I do know what I’m not. And I’m not like you, OK? Or, better, I’m not you. I’m me. Me.’

‘Bernadette, I know this isn’t the time for philosophy, but don’t you see that the “self” is largely a construction based on an “other”? That the self doesn’t exist entirely on its own, but is also built around an external gaze? Since I have been and am part of your existence, my self is a part of your self — and that’s something you’ll never be free of. It can’t be taken back. This is everyone’s hell.’

‘Who do you think you are — some kind of Sartre? You want philosophy? Well, listen up: my self, which may actually contain a part of your self, no longer wants to see itself reflected in this other that is you. By bringing me down to your level, you tried to stop me from having the simplest, most precious, things in the world, Antonym. Where’s the noise of children scampering through the house? Where are the family lunches on Sundays? Where are the holidays on the beach? Where’s that comfortable boredom that people who love one another feel after years of life in common? Where are the plans: for a bigger house, an exotic holiday, a place in the country, for … for … For God’s sake, Antonym, I don’t despise everything middle class! I want to be middle-class, OK? I want to have noisy reactions like this. Do you hear me? Do you want that translated into psychologist crap? Well, here: I’ve smashed the mirror, Mr Narcissus, and in this other self, growing here in my womb, there won’t be any of your self. None at all.’

‘You’re wrong, Bernadette! What hurts me most is knowing that my self — which shaped part of your self — will inhabit the self of the child of this guy who slept with you.’

‘No, Antonym, this is all just another one of your abstractions. What hurts you most is the fact that I’ve got myself a life and fucked another guy. And enjoyed it! A blind man could tell you what you’re feeling. It’s called jealousy. And middle-class jealousy at that. Your story is pretty cock and bull, too, darling. Now get out.’

‘Bernadette, I …’

‘I said, get out. I can’t stand looking at you any more.’

‘Can I take the book?’

‘By all means. You’re going to end up like Ivan Karamazov.’

X

‘You look upset. Wasn’t it any good?’

‘Of course it was … It’s just that I had an argument with my ex that I can’t get out of my head. She’s pregnant to a guy she doesn’t know, and she’s going to keep it.’

‘These ex-wives have always been a headache for me.’

‘…’

‘It’s almost like a dream being here with you, you know.’

‘A nightmare, you mean.’

‘Oh, don’t be so bitter, darling. If Jonah knew, he wouldn’t believe it …’

‘Who’s Jonah, your whale?’

‘Dickhead … A really intelligent guy I went out with years ago. We got along really well. But one day he said he needed to take some time out, travel around Europe. The last night … Wow, it was wild!’

‘Then, bye-bye, Jonah?’

‘Yeah. When the Berlin Wall came down, he’d just arrived in Germany. He even sent me a little piece of the wall. Cool, don’t you think? He wrote a note saying that, unlike socialism, I wasn’t one of his lost illusions. The guy was so fucking creative.’

‘So why

wouldn’t lost-illusions Jonah believe we’re fucking?’

‘Oh, don’t talk like that — “fucking.” We’re having a relationship.’

‘OK, so why wouldn’t lost-illusions Jonah believe we’re relating by fucking?’

‘You’re a lost cause, you know … Because Jonah also really liked your journalism.’

‘So one of my twenty-five readers was a backpacking communist.’

‘There was this news item once about a banker who spent much more on the guard dogs at his branches than his employees. Then you wrote in the paper that that was an apt illustration of the difference between socialists and social democrats: while the socialists wanted the bank employees to earn more than the dogs, the social democrats would be happy if they made the same. Jonah laughed his head off and used to tell it to everyone.’

‘I didn’t write that.’

‘Yes, you did.’

‘What an idiot I was.’

‘Jeez, you’re in a bad mood.’

‘I’ve had it with journalism, but I need to think about what I’m going to do for a living. My job on that in-house paper finishes next month. Hemistich said he was going to make me a proposal … Have you heard anything about that, Kiki?’

‘No. He’d kill me if he knew we’ve been together so many months. Actually, you swore you wouldn’t say anything.’

‘I won’t say anything. But I don’t get why you’re so scared of him. You’re free, I’m free …’

‘I’m not that free. How do you think I pay my bills?’

‘By renting out the properties you inherited. That’s what you told me.’

‘I lied.’

‘You lied?’

‘I lied. I don’t have any properties, and I live in a rented flat. To be honest, I live on what Hemistich pays me.’

‘You’re paid by Hemistich? What does he pay you to do?’

‘To help with what he calls “persuasion tactics”.’

‘Which is …’

‘Having sex with the guys he wants to draw into what he calls his “sphere of influence”. I’m like a continuation of the special events.’

‘You’re a whore.’

‘No need to be insulting.’

‘Does he pay you to go out with me?’

‘He paid for me to go out with you in the first two months. Then he said it wasn’t necessary any more and that I should step away because “the work was done”.’

‘So why do you keep having it off with me?’

‘Don’t you see? I’m in love with you.’

‘But I’m not such a good fuck.’

‘I think you’re great. You know, when we saw each other in the restaurant the first time, I could tell something was going to happen between us. You gave me a special look.’

‘I was looking at your arse.’

‘Pig.’

‘…’

‘Do you love me?’

‘No.’

‘I’m leaving.’

‘Don’t be such a baby, Kiki. I like you a lot. For me, it’s practically the same thing.’

‘Why do you like me?’

‘Because you’re special.’

‘I like the sound of that. Why am I special?’

‘Women are all the same in their flaws, and different in their qualities.’

‘Well …?’

‘Well, what?’

‘What are the qualities that make me different from other women?’

‘These here …’

‘Ah, you’re tickling me, you clown.’

‘Kiki, what do you know about Hemistich’s events that I don’t?’

‘I’m sick of talking about that. Let’s make love again.’

‘Either you tell me or we’re finished.’

‘Do you think Hemistich tells me anything? I know what everyone else involved knows: once a week, he transforms the restaurant into what you saw, and it becomes the venue for an orgy.’

‘That’s all?’

‘That’s all … Well, come to think of it, there has been the odd event outside the restaurant.’

‘Outside the restaurant, where?’

‘In this huge country house about forty minutes out of town.’

‘Hemistich never told me there were events in a country house.’

‘You should’ve seen them! They’d go on for two whole days; total madness. I’d come back a wreck. The upside is that I got paid double to participate.’

‘Do you know when the next one is?’

‘No, I don’t. I think they’ve been on hold ever since Augusto died.’

‘The Augusto that killed his wife and committed suicide?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Did you know him?’

‘Of course I did. But don’t worry. He wasn’t as good as you, darling.’

‘You’re so irritating! I’m not worried about that, you idiot.’

‘Me, an idiot? I’m not telling you anything else. You’ve hurt my feelings.’

‘I’m sorry, Kiki, it’s just that I really want to know more about Augusto. We were friends for a while.’

‘OK, I forgive you. Augusto participated in Hemistich’s events.’

‘Right, so Augusto commits this incredible act of violence, and there hasn’t been an event outside the restaurant since. What’s the connection?’

‘And I’m supposed to be the idiot! Augusto did what he did at one of these events.’

‘I’m shocked. Hemistich didn’t tell me any of this.’

‘Do you think he’d go around blabbing about it?’

‘Did you see them die?’

‘I’m not saying anything else.’

‘Do you or don’t you want to keep seeing me?’

‘Promise you won’t tell anyone?’

‘I promise.’

‘Do you swear on your mother’s life?’

‘My mother’s dead.’

‘Swear on your dad’s life.’

‘He’s not worth it.’

‘Then swear on your mother’s grave.’

‘I swear, I swear. What a drag, Kiki …’

‘I didn’t see them die … It’s hard for me to talk about these things.’

‘Make an effort.’

‘Augusto used to show up alone, but that night he brought his wife. I remember she was really impressed by the décor of the house. The candles everywhere, the same figures as in the restaurant on the walls … Satyrs and nymphs — that’s what they’re called, isn’t it? I’ve never been good at mythology.’

‘So what do you think you saw?’

‘Well, when things had really heated up — people fucking, left, right, and centre — I decided to play a game with two hot guys who were dying to do me. I told them that if they really wanted me they’d have to catch me. I took off running, and they came after me. We ended up heading away from the halls and down a winding corridor that went underground. This corridor seemed to go on forever, and other corridors ran off it as if it were all part of a labyrinth. I think it was a labyrinth. Because I was really wasted (Hemistich’s wine must be laced with some kind of drug), it took me a while to realise the guys weren’t behind me any more. When it dawned on me that I was alone, I was scared — especially because, by that time, there was no light. I froze, panting, for several minutes. I was dizzy, freaked out, and really needed to go to the toilet.

After taking several deep breaths, I started to head back. I went slowly, because each step took so much energy. I was in a really bad way, and lost. I’d gone about thirty metres, when I heard a horrible scream. My heart started racing faster than ever, and I felt as if I was about to faint. I tried to cry for help, but my voice stuck in my t

hroat, like in a nightmare. I was scared stiff, but this time I didn’t freeze. It was the fainting feeling that pushed me forward — if I was going to faint, I wanted to be in the light, and with other people. Feeling my way along the walls, I went a little further, until I noticed a sliver of light at ground level at the end of one of the corridors. It’s coming from under a door. It might be a shortcut back to the halls, I thought. So I headed for the door. Behind it, two men were talking. I pressed my ear to the door and … Oh, that’s enough. I’m going to get myself into trouble.’

‘You pressed your ear to the door and …’

‘One of the voices was Hemistich’s.’

‘What was he saying?’

‘ “It’s over.” I wanted to open the door to get out of that dark corridor, but those words made me hesitate. I don’t know why, but I imagined that the scream I’d heard had come from there.’

‘Well, had it?’

‘I think so. What do you think?’

‘How am I supposed to know? What did you do next?’

‘I got out of there as fast as possible, because I was afraid they’d see me. I found my way back quickly, thank God.’

‘What Hemistich said, was that the only thing you heard?’

‘No, I also heard the other man’s answer.’

‘Let’s have it, Kiki.’

‘ “Nothing’s over. This is just the beginning for us.” ’

‘That’s it?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you recognise the voice?’

‘I recognised it an hour later, when Hemistich interrupted the event to say Augusto had killed his wife and committed suicide.’

‘The voice belonged to one of the guests.’

‘No, it was the priest who Hemistich had just called.’

‘Farfarello.’

‘Farfarello, that’s it. How do you know?’

‘Let’s see if I’ve got this right: Hemistich told everyone he’d just called Farfarello, but you say you heard his voice an hour earlier.’

‘That’s right.’

‘And what did Hemistich say to justify Farfarello’s presence?’

‘He said he’d called the priest to provide spiritual assistance.’

‘For the dead.’

The Day I Killed My Father

The Day I Killed My Father